Maria Longley, GiGL Community Manager

The Nature Fix is a new book by Florence Williams that explores how nature contributes to making humans happier, healthier and more creative and how it can restore our “attention-addled brains”.

Williams moved from Colorado to the metropolis of Washington D.C. and she shares rueful reflections on spotting images of wildlife on the fin tails of overhead airplanes that passed for engaging with the natural world in her new home. In an attempt to understand nature’s effect on our moods, well-being and thinking, she talks to (and participates in experiments with) psychologists, neuroscientists, immunologists, anthropologists, and epidemiologists. Scientists of all descriptions in several labs and countries share their work, looking at the physiological and mental changes that make our brains need nature.

Frederick Law Olmstead, co-designer of urban parks such as Central Park in New York and Golden Gate Park in San Francisco, said in 1865 that viewing nature “employs the mind without fatigue and yet exercises it; tranquilizes it and yet enlivens it; and thus, through the influence of mind over body, gives the effect of refreshing rest and reinvigoration to the whole system.”

But is this to do with the biophilia hypothesis, expounded by E.O. Wilson, that we feel at home in nature because we evolved from it, or because stress relief offered by nature restores our brains?

Williams’ entertaining account of a search for answers takes us to Japan and South Korea where the forest agencies run forest therapy trails and hire forest healing instructors; through to Finland where the recommended minimum nature dose for staving off depression is five hours per month. And then onto accounts of what happens to our brains during extended immersion in nature for people suffering from PTSD or children with ADHD. Williams explores what science has to say about the effects of different doses of nature on humans, but it is hard to escape the conclusion that we all benefit cognitively and psychologically from trees, water, and green spaces.

In the final and all too brief section, Williams brings attention back to what all this might mean to city dwellers. There are many insights in this book that could inspire better landscaping of our environments, better policy making in our cities, and valuing more of what we all need.

In London, a report published in January this year by the London Assembly Housing Committee, At Home with Nature: Encouraging biodiversity in new housing developments, focussed on ensuring that London maintains and improves its current levels of biodiversity. Across Europe some cities have explicitly introduced a planning tool called “green space factor” to ensure a minimum level of greenery in new developments.

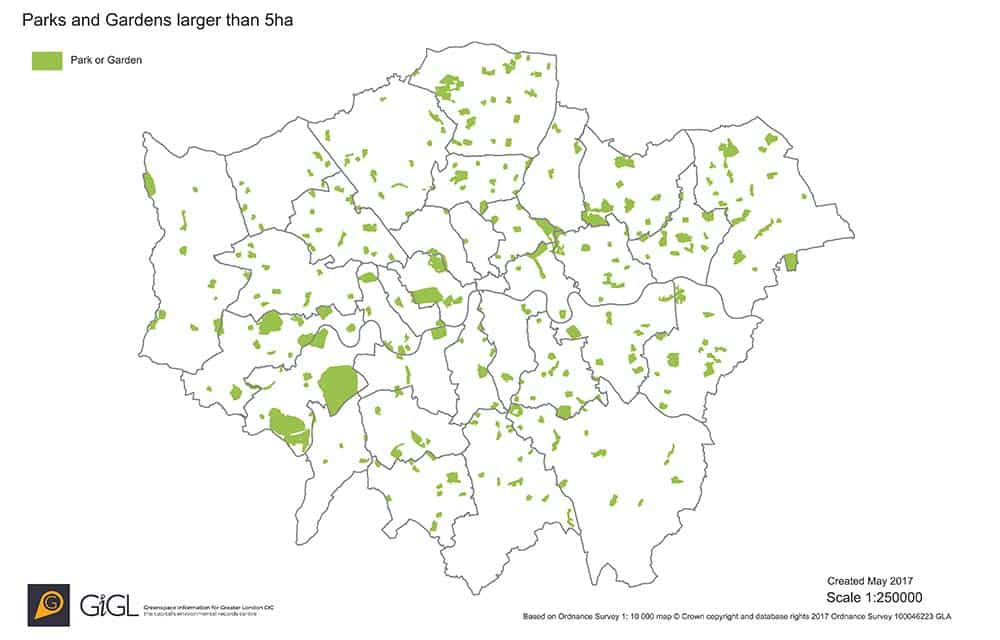

Research discussed in the book suggests that just 15-45 minutes in a city park is enough to improve mood and feelings of restoration. And that large urban parks of more than 5 hectares have positive well-being effects on urban dwellers. For reference, Trafalgar Square is about one hectare.

Parks & Gardens. Scale at A3

In The Nature Fix, Singapore is held up as one of the most “biophilic cities” in the world. Williams contends that to get greenery into all neighbourhoods, you need a strong governing vision. Singapore’s ambition is to have 80% of all people living within 400m of green space. Currently, 70% of Singapore residents are living within this target metric. In London, the London Plan recommends that all residents should live less than 400m walking distance from a designated local, small or pocket park. GiGL have been mapping the areas of London that fall outside of this recommendation as a way of practically providing a tool for local decision-makers to meet this ambition.

The importance of trees and forests is highlighted throughout the book. The London i-Tree Project, one of the largest city tree surveys of its kind in the world, provided base line data on the ecosystem service benefits of the city’s urban forest. The green infrastructure task force report for London identified some of the long-term approaches to delivering our future needs, and The Nature Fix gives good reasons for planning ahead. Cities around the world are integrating more green space into their fabric, and our oft-quoted statistic of 47% of London being greenspace is well-worth celebrating.

Although The Nature Fix looks at nature purely in terms of human benefits, this is an additional angle to the conversation of urban nature and the wider rewilding conversations currently happening in the UK. Williams makes a compelling argument that nature is good for us, which is surely another reason for taking it seriously.