Pollinating London Together (PLT) is a charity dedicated to protecting London’s pollinators and promoting biodiversity. Founded in 2020 by the Worshipful Companies of Wax Chandlers and Gardeners, PLT began as a livery collaboration and has since grown into a vibrant citywide network uniting livery companies, businesses, schools, and community organisations. Now an independent charity, PLT raises awareness of pollinator decline and leads practical initiatives to create and connect green spaces across London. Supported by Community Infrastructure Levy Neighbourhood Fund grants from the City of London Corporation, PLT is developing biodiversity corridors to ensure pollinators can thrive across the capital.

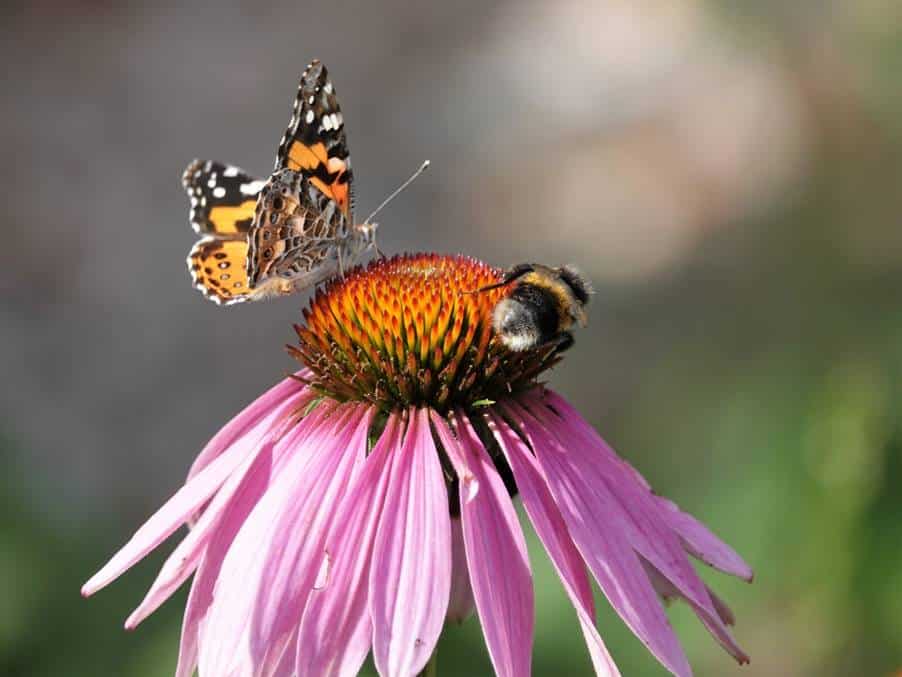

London is full of mini wildlife. Amongst the trees, parks, gardens, railway cuttings and the cracks in pavements, thousands of pollinating insects are at work. Bees, hoverflies, butterflies, moths and wasps move between flowers, transferring pollen and making fruit, seeds and crops possible. Pollinators underpin the health of our wild plant communities and contribute billions of pounds to agriculture across the UK. Yet their habitats are under pressure from climate change, pesticide use and the steady spread of concrete.

At Pollinating London Together, we are working with GiGL to better understand how pollinators use the capital. GiGL has provided us with a detailed analysis of the City of London’s green spaces. This includes information such as tree cover, concrete cover and site-specific features. Eventually, we will use this data to explore what drives pollinator abundance and diversity across the city. For example, we may be able to see at what point increasing concrete cover starts to reduce the number of pollinators present, or whether certain types of green space are particularly valuable.

While our research will take time, the message is already clear: more connected, healthy green space is good for pollinators. And you don’t need to wait for the results of our analyses to take action. Every garden, balcony, community space and allotment can play a role. By thinking about what pollinators need, and making small changes, you can turn almost any space into beneficial habitat.

What is a pollinator?

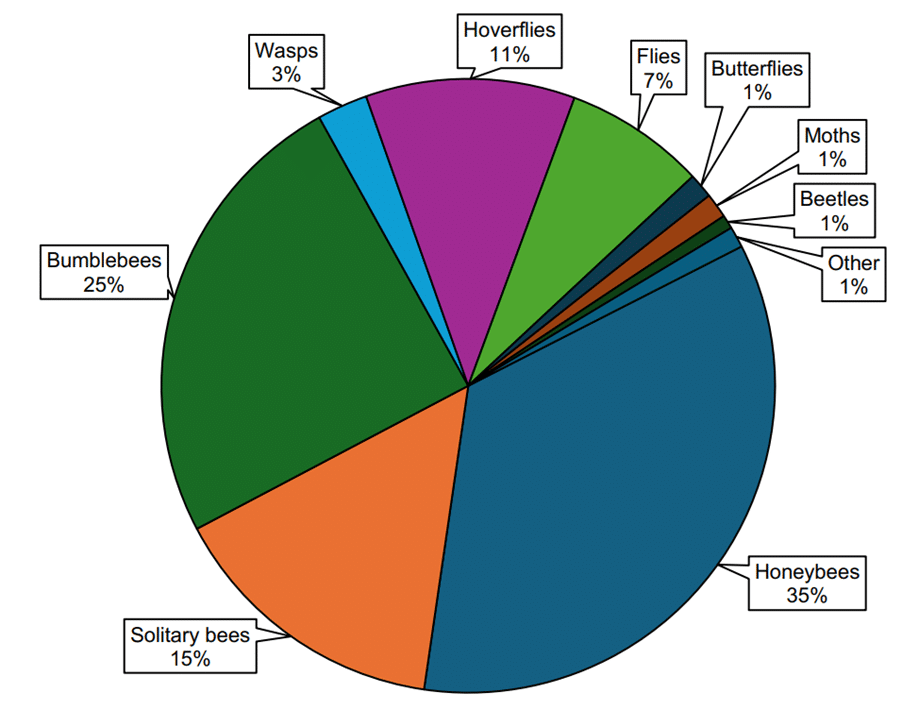

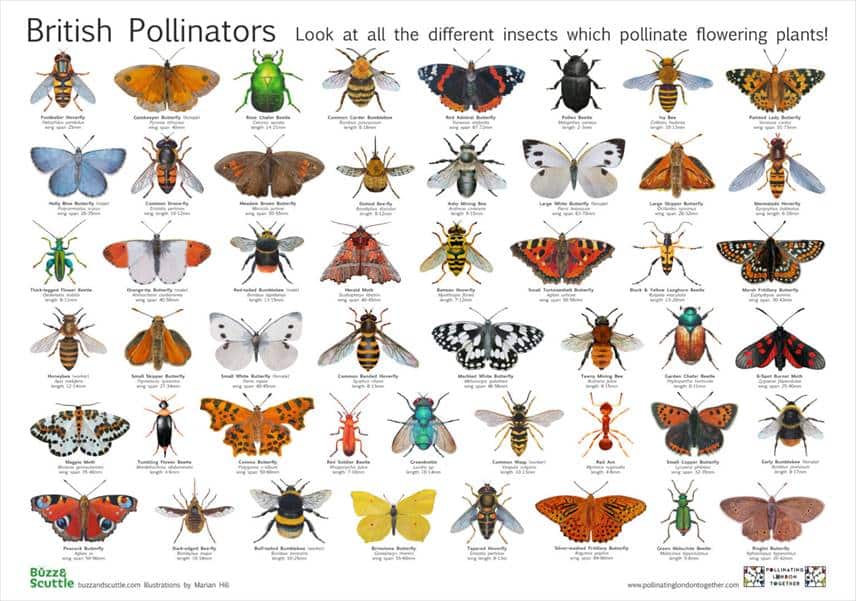

A pollinator is any animal that transfers pollen between flowers, helping plants to reproduce. In London, the most familiar pollinators are honeybees and bumblebees, but they are far from the whole story. Over 250 species of bee live in the UK, including solitary species such as the red mason bee (Osmia bicornis). Hoverflies, often mistaken for wasps, are also efficient pollinators. Butterflies, moths and even some beetles contribute to pollination too.

Not all pollinators are equally efficient. Some, like long-tongued bumblebees, are superb at pollinating deep flowers such as foxgloves. In London, you are most likely to see species such as the buff-tailed bumblebee (Bombus terrestris), common carder bee (Bombus pascuorum), solitary bees such as the common yellow-faced bee (Hylaeus communis), and hoverflies like the marmalade hoverfly (Episyrphus balteatus).

What do pollinators need?

Pollinators need two main things: food and shelter. By providing these, we can support a wide range of species.

Food

The most obvious resources pollinators need are nectar and pollen. But it isn’t enough to plant flowers that bloom all at once. Pollinators are active from early spring through to late autumn, so it’s important to provide a sequence of flowers throughout the year*.

- Spring: Crocuses, lungwort, willow and fruit trees provide early forage when queens are emerging from hibernation.

- Summer: Lavender, catmint, marjoram, sunflowers and knapweed are excellent sources of nectar and pollen.

- Autumn: Ivy is one of the most important late flowers in the city, along with plants such as sedum.

*you can find a more detailed list on our website: https://www.pollinatinglondontogether.com/guides/.

Equally important is the fit between flower shape and pollinator. A bee with a long tongue can reach into tubular flowers like honeysuckle, while shorter-tongued bees prefer open flowers such as daisies. By planting a mixture, you can cater for more species.

Food does not just mean nectar and pollen. Some pollinators, such as butterflies, need specific plants for their young. The caterpillars of peacock and small tortoiseshell butterflies, for example, feed on nettles, while cinnabar moth caterpillars rely on ragwort. These host plants are often dismissed as weeds, but without them these insects cannot complete their life cycles. Leaving a patch of nettles or allowing ragwort in the right places can be one of the best things you do for pollinators.

Hoverflies also play a dual role. While adults feed on nectar, many of their larvae are natural pest controllers, consuming large numbers of aphids. By encouraging hoverflies, you are supporting both pollination and natural pest control.

Shelter and nesting sites

Pollinators also need safe places to rest, hibernate and reproduce.

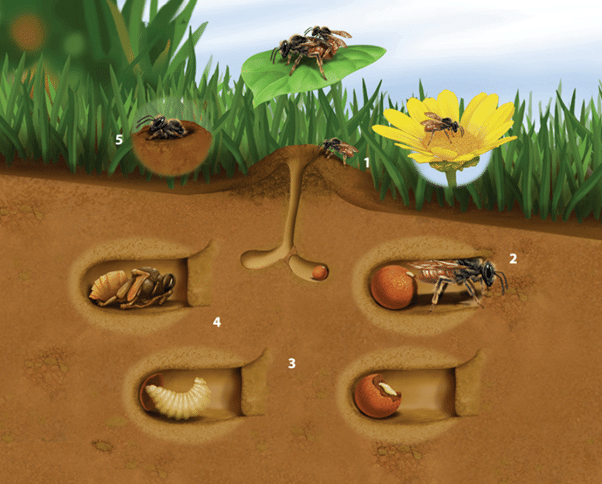

- Bee banks: The majority of solitary bees nest in the ground. Creating a bare patch of soil, ideally south-facing and using sandy loam substrate, can provide nesting sites.

- Insect hotels: Other solitary bees, such as mason bees and leafcutter bees, nest in cavities. Bee hotels, made from bundles of hollow stems or drilled wooden blocks, can provide these. Placement matters: they should face the sun, be raised off the ground, and have holes of varying diameters to suit different species.

- Hoverfly lagoons: Certain hoverflies lay their eggs in shallow water, where their larvae (some known as rat-tailed maggots) develop. A simple container of stagnant water with organic material, placed in a sheltered spot, can provide this unusual but valuable habitat.

- Log piles and undisturbed corners: Dead wood supports a host of invertebrates, many of are pollinators. A log pile in a shady corner will also serve as overwintering shelter for insects

GiGL’s data shows us where green space already exists and what form it takes. Our role is to link that information with on-the-ground surveys of pollinators. In time, we will be able to see patterns such as whether areas with more tree cover support greater pollinator diversity, or whether pollinators decline past a certain threshold of concrete cover.

This knowledge can guide policy and planning. But just as importantly, it highlights how small-scale actions connect with the bigger picture. A balcony with herbs, a garden with a log pile, or a school with a patch of wildflowers adds to the city’s network of habitats. When many people make these choices, the result is a patchwork of resources across London.

What you can do today

You don’t need specialist knowledge or a large garden to make a difference. Start small:

- Plant a pot of lavender or thyme on a balcony.

- Leave a corner of nettles for butterflies.

- Drill holes in a log or put up a bee hotel.

- Allow ivy to flower in autumn instead of cutting it back.

- Resist the urge to tidy every patch. Messier gardens are often more wildlife friendly.

Pollinators thrive when we give them the basics: food, shelter and space. London’s pollinators are resilient, but they need our help. Every patch of green matters. Together, we can make sure the city remains a place where both people and pollinators flourish.

By creating and protecting these habitats, we can ensure that London remains a city alive with bees, butterflies and hoverflies. And with the help of GiGL’s analysis, we will soon understand even more about how to make that happen at scale.