Kevin Martin is a Research Fellow at Urban Plant Lab. He serves as the Head of Tree Collections at the Royal Botanic Gardens Kew, where he is responsible for curating the tree collection. Kevin, along with Andy Hirons (Director at Urban Plant Lab and a Senior Lecturer in Arboriculture and Urban Forestry at University Centre Myerscough), delivered research into the Future Climate Suitability of London’s Public Realm Trees.

London’s trees are more than just green spaces, they are essential infrastructure. They cool our streets, filter our air, manage stormwater, and provide habitats for countless species. Yet the climate these trees were planted for is changing faster than ever before. Hotter, drier summers, warmer and wetter autumns, milder winters, and more frequent heatwaves are already testing the resilience of the city’s urban forest. If we continue planting and managing trees as we have in the past, much of London’s canopy could struggle or disappear by the end of the century. The challenge is clear: to secure the benefits of trees for future generations, we must use data, climate projections, and plant biology to select species that can survive and thrive in London’s changing climate.

In November 2025, Urban Plant Lab delivered research and a final report looking into the Future Climate Suitability of London’s Public Realm Trees. The report, commissioned by the Greater London Authority and the Forestry Commission assesses how well London’s publicly owned trees are likely to cope with projected climate conditions in 2090. London is the first city in the world to commission such a comprehensive climate suitability assessment of its public trees, putting it on the front foot with the evidence needed to act early and strategically.

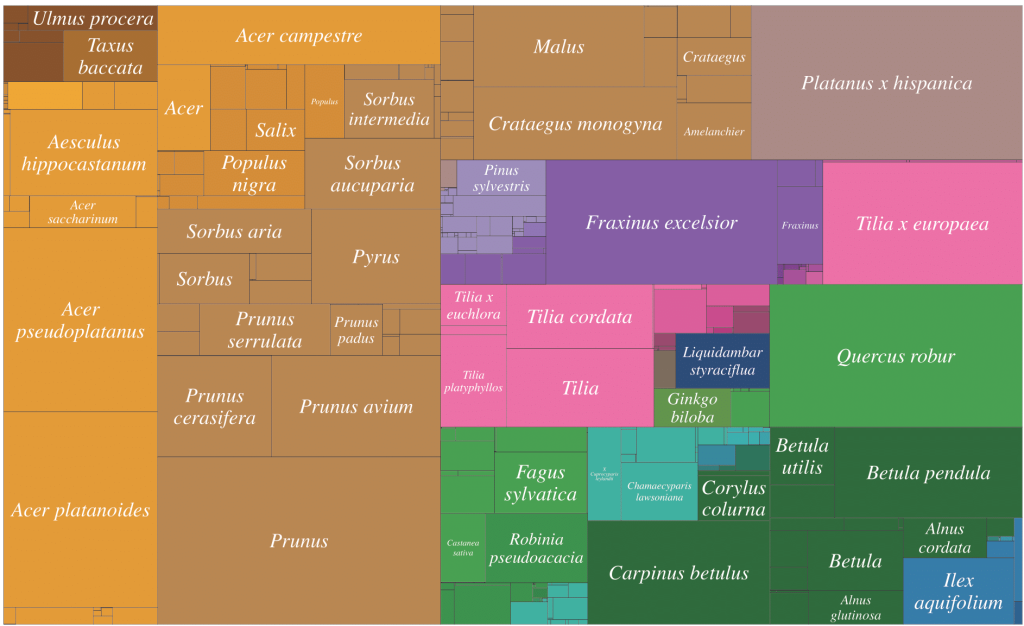

The research utilises the newly updated London Public Realm Tree Map – a dataset that GiGL has compiled and refined as part of a GLA project. GiGL coordinated the task of gathering records from public tree maintainers across the city, including 32 London boroughs, the City of London, Transport for London, the Royal Parks, the London Legacy Development Corporation (Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park), and Quintain (Wembley Park).

The report aims to challenge how we think about tree selection and to test the approaches we rely on when planning London’s urban forest. London is a global city that has long been recognised for its innovation from the infrastructure that allows millions to move around efficiently, such as the Underground network, to the extensive green spaces and public parks that define the city’s character. These innovations have shaped a city where people can live comfortably and, in many ways, thrive.

Yet this same drive for growth and mobility has also had unintended consequences. The density of buildings, transport systems, and the energy required to sustain modern life has contributed to the creation of powerful microclimates. The Urban Heat Island (UHI) effect where cities become significantly warmer than surrounding rural areas is now accelerating, amplified by the impacts of a rapidly changing climate.

“Urban trees are a frontline adaptation tool providing cooling, shade, air quality improvements, stormwater regulation, and essential biodiversity support”

We are already feeling these changes. If we pause for a moment to reflect on the last 30 years alone, the transformation is remarkable. Average UK temperatures now regularly exceed 10°C as a mean annual temperature, and the frequency of extreme heat events is rising. These trends are reshaping our landscapes and placing unprecedented pressure on urban trees, many of which were planted for a climate that no longer exists.

The Research

The study analysed over 1.1 million public trees across London, assessing each species for its suitability to the projected 2090 climate using a composite scoring system that combined global species distribution data with plant trait analysis. Species were grouped into four climate suitability categories: high suitability (likely to thrive), moderate suitability (may perform well, especially if sourced from regions with compatible climates), low suitability (expected to struggle), and vulnerable (unlikely to survive or thrive).

To understand which trees might still thrive, we must look beneath the bark, into the functional traits that determine how species cope with heat, drought, and other stresses. Traits such as turgor loss point provide a window into drought tolerance. Wood porosity determines a tree’s vulnerability to hydraulic failure during dry periods. Leaf characteristics, including LDMC (leaf dry matter content), reveal how well a species can maintain function under prolonged drought. Even growth rate and canopy structure matter, as trees that efficiently cool the air will provide essential climate-regulating services as heat intensifies.

When we combine these physiological insights with Species Distribution Models (SDMs), a clearer picture emerges. Modelling allows us to map how future temperature and moisture regimes intersect with the biological limits of each species. Patterns begin to emerge: some species that are iconic in London today may struggle as drought stress increases, while others currently overlooked show remarkable resilience under projected future conditions.

The results are both sobering and hopeful. Many familiar species possess traits that leave them vulnerable to hotter, drier summers and prolonged heatwaves. Their decline may not be immediate, but over time, reduced growth, canopy dieback, and even premature mortality are likely. At the same time, the models highlight species that have the physiological “toolkit” to withstand the challenges of a hotter, drier city. These species, though often underused today, could form the backbone of a resilient London urban forest by 2100.

Even within familiar genera, differences can be profound. In Tilia, for example, species vary widely in moisture and temperature tolerance. Some show excellent suitability for London’s future climate, while others become marginal. This nuance reinforces an important point: tomorrow’s planting decisions cannot rely on tradition or aesthetics alone. Understanding species traits, climate thresholds, and projected environmental conditions is essential if London’s canopy is to endure.

The Findings

Key findings highlight the scale of the challenge: if no changes are made, 73% of London’s public trees may struggle to thrive or survive. Only 0.38% of current trees are considered highly suitable for future climate conditions, 22% have moderate suitability, 62% are rated low suitability, and 10.6% are considered vulnerable. Publicly owned trees deliver around 60% of the ecosystem services London’s urban forest provides including cooling, air purification, and stormwater management—making their future health critical for sustaining both environmental and cultural benefits.

The implications of these findings are profound. Trees poorly suited to future conditions may grow slowly, be more vulnerable to pests and pathogens, and die prematurely, reducing the many benefits they provide. Yet the report also highlights significant opportunities to strengthen London’s urban forest through strategic action.

Recommendations include:

- Enhancing the health of existing trees

- Diversifying species to include those suited to projected future climates

- Funding tree establishment rather than simple planting

- Collaborating with nurseries, developing mechanisms to bring novel plant material into horticultural production

- Addressing gaps in plant trait data

- Evaluating potential canopy cover impacts and implementing city-wide strategies to manage the urban forest holistically

Another key recommendation is adopting a tree data standard for London. Even with sophisticated models and trait datasets, practical challenges with tree data can hinder decision-making. In London’s publicly owned tree dataset, there are multiple inconsistencies due to the vast number of data suppliers using different systems and recording methods, including discrepancies in naming standards. Standardisation ensures that species data are consistent across nurseries, councils, and research projects, enabling more precise climate suitability assessments and better-informed urban forest planning.

The Future

As the world looks towards COP30, the global conversation is increasingly focused on adaptation alongside mitigation. While reducing emissions remains essential, cities like London must also adapt to the climate that is already unfolding. Urban trees are a frontline adaptation tool providing cooling, shade, air quality improvements, stormwater regulation, and essential biodiversity support.

COP30 is expected to, urging cities to use data-driven, evidence-based planning. For tree selection, this means moving beyond tradition, preference, and legacy planting lists, and instead grounding decisions in climate modelling, species distribution data, soil moisture projections, and physiological thresholds such as drought tolerance and heat resilience. When we use high-resolution climate models to look ahead to 2100, the London they reveal is not the one we know today.

Changes don’t just affect human comfort or energy demands; they reach deep into the biology of the trees that line our streets, parks, and squares. Trees, rooted in place, cannot seek shelter or move to cooler ground. Their survival depends entirely on how well their physiology matches the climate around them. As that climate changes rapidly, pressures on them intensify, posing risks to the ecosystem services they provide and the character of the city’s treescapes.

Ensuring the resilience of London’s trees requires collective action. By working together, with organisations such as GiGL, and applying a data-driven approach that integrates climate modelling with functional trait analysis, London can maintain healthy, diverse, and resilient treescapes that continue to provide essential benefits for generations to come.