The open data movement is inspiring and exciting, but for it to work for the environmental data sector it needs long-term and significant investment in our local, regional and national data infrastructure

The Open Data Institute (ODI) defines open data as “data that anyone can access, use or share”. In this article we set out our position on open data and plans for the future, highlight the difference between ‘shared’ and ‘open’, and offer expert opinion from the team on open data that are available via various online portals.

GiGL Policy

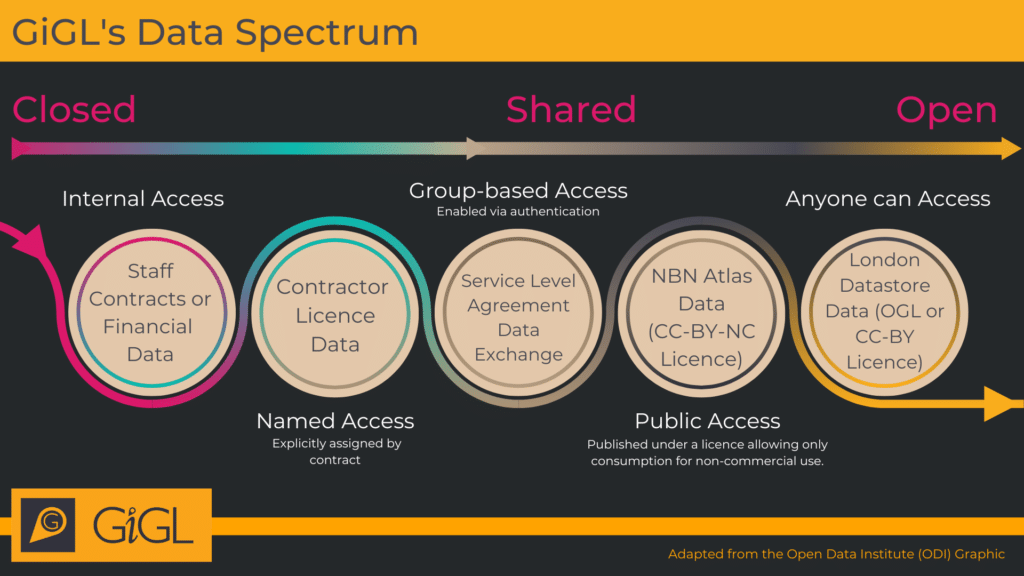

The Data Spectrum devised by the ODI, illustrated below, lays out the language of data to help us understand different levels of access and licencing.

For further information on shared and open data licences, please see https://creativecommons.org/licenses/

GiGL operates under a shared data business model, which means our detailed and up to date data are publicly accessible via our free and charged services, but end uses are restricted by licensing terms to protect data flow and our business. We also publish open data to act as a shop window for our services. We’ll explain how we got to this model in a moment, but first we want to highlight the range of GiGL open data already out there.

GiGL’s Open Data

GiGL publishes datasets using open data licences to improve consumers’ understanding of London’s natural environment and raise the profile of our services. The open datasets are blurred spatially, restricted temporally, or are less detailed than the high quality datasets that underpin our services. We do not publish open data without express permission from the data owners, and notify all partners of open data publication as part of our ongoing services.

At GiGL, the licences we use for our open datasets are the OGL (Open Government Licence) and CC-BY (Creative Commons Attribution licence). The only restriction placed on consumers by these licences is that they must give attribution to GiGL as the data source, which means consumers can republish and make money from the corresponding data.

A full catalogue of GiGL’s current open data can be found in the table below, along with some alternative sources of related open datasets and their potential issues. GiGL’s complete, current and most accurate versions of these datasets are available under licence via a Service Level Agreement (SLA).

| Dataset | GiGL Open Data | Alternative Sources of Open Data and their Potential Issues |

|---|---|---|

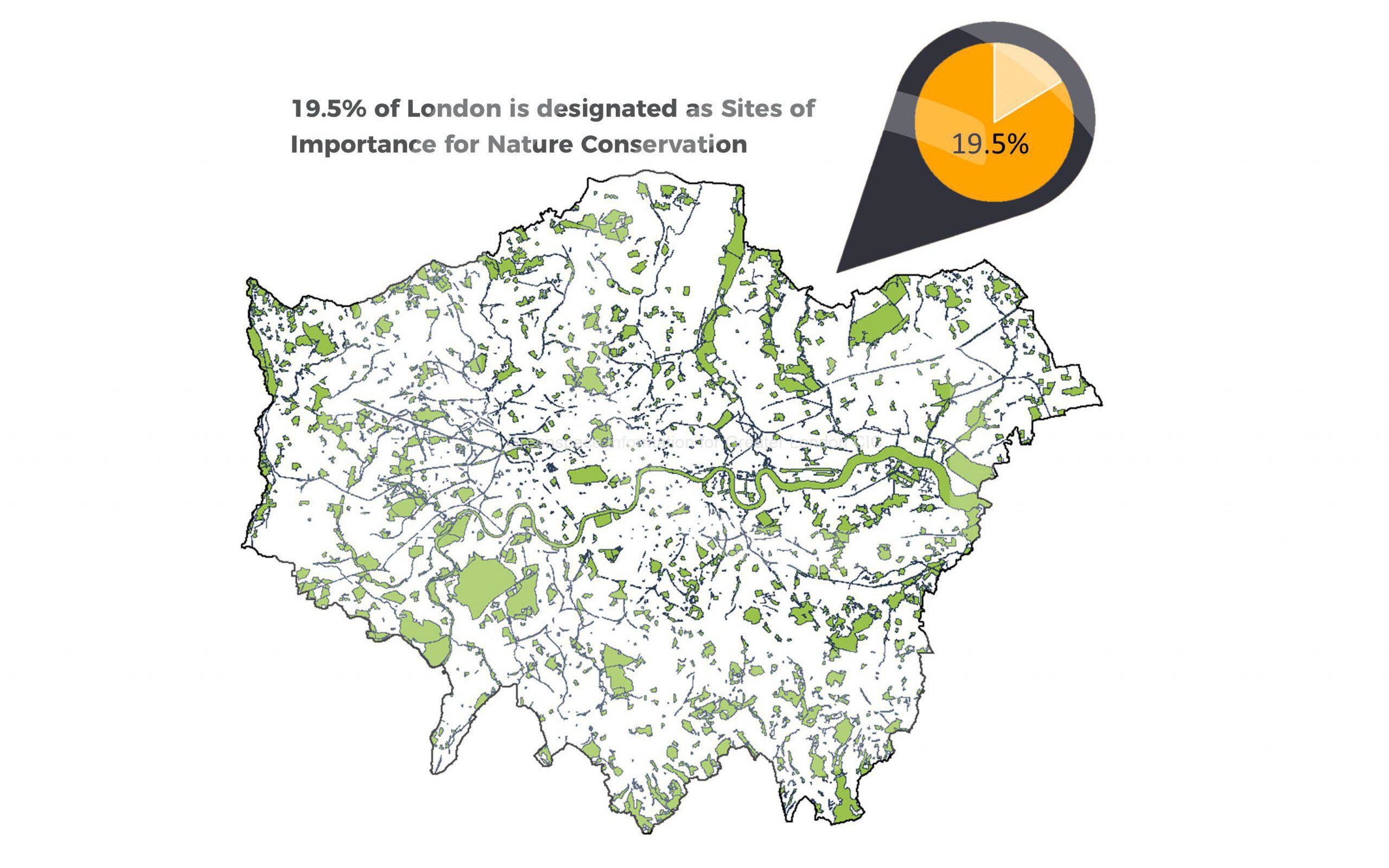

| Sites of Importance for Nature Conservation (SINCs) | Via the London Datastore. This is updated on an annual basis with a version from the previous year, with reduced attributes | |

| Public Open Spaces (POS) | Due to release open version by the end of 2023-24 financial year | Some available via local authorities but may not be as comprehensive as GiGL’s |

| Areas of Deficiency in Access to Nature (SINC AoD) and Areas of Deficiency in Access to Public Open Space (POS AoD) | Due to release some statistics regarding AoD per borough or ward | |

| 800m AoD | Via the GLA website at polygon level | |

| Privately Owned Public Spaces (POPS) | Via the London Datastore | |

| Open Space | Spaces to Visit and Friends Group subsets via the London Datastore. Both are updated on a quarterly basis | Partial data available from local authorities but may have poor coverage |

| Habitats | Natural England Priority Habitats layer. Only holds priority habitats and may be out of date or incomplete in many areas | |

| Species | Species records will be added to the NBN Atlas (with permission) at 10km/2km resolution to act as a signpost for better resolution data held by GiGL | See GiGL website here for list of 3rd party open species data. Some issues include: use restrictions; lower resolution; lack of verification/validation by verifiers; difficulties in amalgamating different sources of data due to differing formats ; potential duplications |

| Trees | Some data are currently available on the NBN Atlas. This dataset has not been updated or added to since it was uploaded in 2018. It is an amalgamation of GLA habitat survey data and LB street tree data | |

| Green Belt and Metropolitan Open Land (MOL) | Via the London Datastore from the GLA. GiGL update and manage Greater London’s Green Belt and MOL data so these alternative datasets may be out of date and incomplete | |

| Statutory Sites (SSSI, SAC, SPA, Ramsar, NNR, LNR) | LNRs are available via Natural England. We review this dataset and add missing sites. The revised data are made available by GiGL services |

Third Party Open Data

There are several other open datasets and platforms out there which are not directly related to GiGL, but may be helpful for those working in ecology and biodiversity. Although these open datasets have their benefits for being publicly accessible, there are several limitations surrounding the quality and accuracy of the data. GiGL has been evaluating the quality of these datasets using criteria developed by the Data Management Association UK (DAMA) and the full summary can be found on our website here.

One of the datasets we have been assessing is the Ancient Woodland Inventory (AWI) from Natural England. This identifies over 52,000 ancient woodland sites in England. However, important areas of Ancient Woodland in Greater London are missing as they were too small to meet the mapping criteria. GiGL is currently working on updating the AWI, assisted by national partners such as Natural England and Woodland Trust, to create a thorough and complete record of all Ancient Woodland in London. You can read more about this project here.

Natural England have also produced a Living England Habitat map, which can be accessed here. This was created using satellite imagery and algorithms to predict the likely habitat found in an area. It may be suitable for national scale analysis but the spatial granularity of the data and the known accuracy issues in habitat identification, particularly in urban areas, makes it less appropriate for fine scale analysis within London. GiGL is currently working on improving our own habitat dataset that will be vital for use in projects involving Biodiversity Net Gain (BNG) and Local Nature Recovery Strategies (LNRS). Using on-the-ground knowledge and GIS, evidence-based conclusions can be made about habitats and their biological significance.

There are many data portals available for viewing and downloading species data, all with varying levels of quality and permitted end uses. In addition to potential issues at the data generation and capture stages, the quality of the data is also dependent on their resolution; the verification techniques used, or lack of them; and possible presence of duplicated data. A full summary of the species data portals known to GiGL can be found here.

How We Got Here

We joined the ODI in 2016 to help us to better understand the global open data movement, which is motivated by the potential of open data to drive social, economic and environmental benefits, and to see if we could play a small role in it given we are a social enterprise with similar goals. We had meetings with ODI to discuss the pressure being put on our sector to move to an open data approach as a result of their work with Defra. We attended training sessions to get to grips with open data business models, went to their excellent ‘open data summits’, and researched organisations the ODI felt were working in a similar way to how GiGL could if we switched to a fully open data approach.

While exploring options with the ODI, we unexpectedly lost a key contract with a national partner. They cited their priorities to promote access to open data as one of the reasons, which highlighted to us the importance of our work with the ODI.

In 2017, we organised a workshop led by the ODI for members of the Association of Local Environmental Records Centres (ALERC). The ODI’s recommendations from their ‘Making Open Work’ report, which summarised the workshop, included engagement with Defra to discuss how they could cover the full cost of our sector releasing capture resolution open data; releasing discovery datasets of hotspots and wildlife sites; reducing costs by collaborating on delivery mechanisms within our sector; and better showcasing the value of records centres to stakeholders.

In 2018, the Treasury released a discussion paper titled ‘The Economic Value of Data’. It builds a strong case for many private and public sectors, particularly transport, to release and consume open data, but is also very clear that it won’t always be appropriate. It specifically states that open data isn’t appropriate or beneficial for all forms of data, including ‘…where data is already monetised, and where making it open would remove a source of income. This could harm business models which use resale to invest in better data gathering, and in the public sphere, could result in taxpayers replacing lost revenue.’ Whilst we don’t charge for data, and never have, we do charge some stakeholder groups for services that enable access to data as we believe they should contribute to the ongoing data stewardship that they directly benefit from. These services include the provision of datasets that we update and improve daily, as well as various information and answer services tailored to the data end use, and bespoke outputs based on our partners’ specific requirements.

Our approach of charging for services helped us move from being dependent on grant funding, one-off contracts and the generosity of London Wildlife Trust as our host, to sustainably covering our running costs for three members of staff and the wider business requirements by 2004. Subsequently all profit has been invested in developing our data stewardship work, and we now have fourteen staff focused mainly on nurturing relationships with data producers in our community and professional networks, and updating and improving all of our core datasets and systems. In our experience, the majority of those we work with don’t have the time or sometimes the skills to mine the data for answers themselves while also trying to make sense of the metadata and licence terms. With this in mind, we have also invested in staff to help our partners and clients get the insights out of the data that they need to answer their questions and inform their work.

Since the advent of open data, several national, regional and local organisation have sought to move us to an open data approach. Their suggestions tend to focus on the process of making data open, rather than how it would be funded or making a case for the benefits of doing so to the natural environment, to them as stakeholders, or to our social enterprise. Suggestions have included publishing all data under an open licence to see how it goes, and publishing them to create competition for our services. Neither make business sense, as the likelihood is that our partners and clients would consume our open data ‘free’ via online platforms, or pay for access via other service providers who are able to monetise our datasets without contributing to the costs of getting them to the point of use. Either option would result in the income from our services being lost, and our investment in updating and improving our datasets potentially coming to an end. We aren’t prepared to take this risk as our work is essential to the protection and improvement of London’s natural environment and the related benefits to Londoners.

Our colleagues in other records centres have also recently spent time investigating misuse of shared data made available for non-commercial use via the National Biodiversity Network’s (NBN) Atlas. Potential clients of their services are using shared data from the Atlas to inform planning applications and other activities they are paid to undertake, when they shouldn’t be accessing or even viewing data published under the CC-BY-NC licence at all. The lack of capacity of the licensors and recipients, such as local planning authorities, to monitor breaches means that they are not investigated and decisions are not based on the best available evidence base, which in turn can impact negatively on the natural environment.

So What’s Next?

There are a few more open data projects in the pipeline for us that will be shared via our website, the London Datastore and the NBN Atlas. They will be discovery datasets that help people find us and raise our profile and will be useful at a national and international scale. They will enable GiGL to offer app developers a resource they can use to build wellbeing and nature-related apps. We will also update and extend our ‘Key London figures’ on our website, and will release an accompanying open dataset that sets out the stats on a ‘per ward’ basis for use in publications and by the media.

We will also continue to assess third party open data sources and signpost our stakeholders to them with a simple assessment of their usefulness based on factors such as metadata, completeness and update schedules (adding to our webpage here), as well as absorbing high quality open data into our core datasets to save our stakeholders time and effort.

We are exploring the creation of volunteer roles to help us investigate the scale of shared data licence breaches by organisations working in London, which are likely impacting negatively on our services, so we can raise awareness of the issues with national organisations such as ALERC and its members, the National Biodiversity Network Trust (NBN), and NBN members. We are also keen to work with ALERC and the NBN Trust on addressing the issues through raising our stakeholders’ awareness of best practice use of data. We will also seek to influence key players in London to ensure they are all aware of what is happening and what it likely means so they can assess planning applications and other outputs accordingly. If the scale of the problem is as big as we anticipate, we will ask that the NBN Trust’s fines for breaching licences on the Atlas are issued where necessary.

We will continue to work hard to make a profit so that we can invest it per our commitments as a not-for-profit social enterprise, which require us to invest profit back into the community we were set up to serve. In the short-term we aim to develop the team and our systems to further increase our capacity for data stewardship as well as with our professional and community networks to provide the support in using the shared data that they need. Our next phases of investment will include paying for access to external data that will improve what we can do for London, and eventually we aim to fund a survey and monitoring programme that will involve Londoners in community science, fund the work of the many experts we currently rely on providing time free of charge, and result in data on species, habitats and open spaces that can reliably show how London’s natural environment is faring.

We will be even better at helping our stakeholders understand the full costs of what we do and why we choose to work using a shared data business model rather than a fully open approach, with the hope that this will turn them into ambassadors for what we do. This will include articulating the benefits of a shared data approach to them, and how working in this way creates social value and ensures investment back into what we do for the benefit of nature and Londoners. An open data approach would create competition, but based on our recent observations a lot of new private sector businesses would emerge with sleek looking platforms that monetise data without investing in them. Unlike social enterprises, private sector businesses’ profit only benefits the business owner, the shareholders and investors, meaning the limited money that is currently available and invested into our sector is lost.

In anticipation of receiving a well thought through proposal for moving to an open data business model, we have devised a method of calculating how much GiGL invests annually in data stewardship, so we can provide a clear cost in our response and demonstrate the value of working with us to our stakeholders. Last financial year it was approximately £500,000, which amounts to a benefit to cost ratio of about 5:1 for local authorities with an SLA, and as much as 50:1 for our regional partners, even before the work we do to support them in using the data, or the additional environmental, social and economic benefits of working with a social enterprise are factored in. This work was inspired by the Geospatial Commission’s ‘Mapping the Species Data Pathway: Connecting Species Data Flows in England’ report from 2021, which shows that the benefit of the work of the members of the NBN and others far outweighs the costs, and is well worth a read.

If we do receive a proposal to move to an open data business model, we will consult with our partners, clients and other stakeholders who support our current approach to ascertain if they want us to take what we currently feel is a significant risk to the services we currently provide them. The consultation will be based on the likely reduction in capacity to deliver our data stewardship work and information and answer services that are business critical to many organisations in our professional networks, as well as important to the community networks and local activists that use our services to help them protect and defend nature in the capital. The results will be used by our Board to inform their response, and how much funding they will ask for to ensure the services our stakeholders rely on continue, and we don’t lose the opportunity to fund the survey and monitoring programme we see as an essential step (or two) in our evolution as a service provider that benefits nature and people in the capital.