Following last month’s initial article in our series on recording apps, the second instalment is here with a brief overview of iNaturalist and specifically iNaturalistUK. With the iNaturalist-based City Nature Challenge fast approaching later this month (26th – 29th April), learn why the app has become an essential part of the toolkit for new recorders worldwide and how to get involved!

The original American iNaturalist humbly began in 2008 as a Master’s project, to act as a ‘crowdsourced species identification system and an organism occurrence recording tool’. But it is undoubtedly the ‘online social network’ [1] aspect of the app that has popularised it across the world and helps iNaturalist to achieve its primary mission in ‘increasing natural history literacy, understanding, and interest among the public’ [2]. iNaturalistUK formally took on this mantle in 2021, with the UK-based website sitting within the 23 organisation-strong, iNaturalist network across the world. The devolved network of iNaturalist partners helps the biodiversity data collected to be locally used better; the iNaturalistUK managing partners – the National Biodiversity Network Trust (NBN Trust), Marine Biological Association (MBA) and Biological Records Centre (BRC), are better placed to responsibly access and manage precise geolocation information for protected species than a global body attempting to understand local designations.

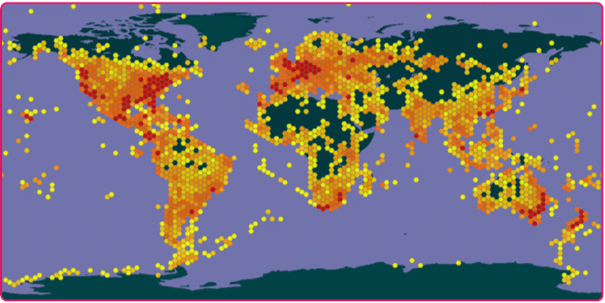

iNaturalist.org. Occurrence dataset https://doi.org/10.15468/ab3s5x accessed via GBIF.org on 2024-04-11.

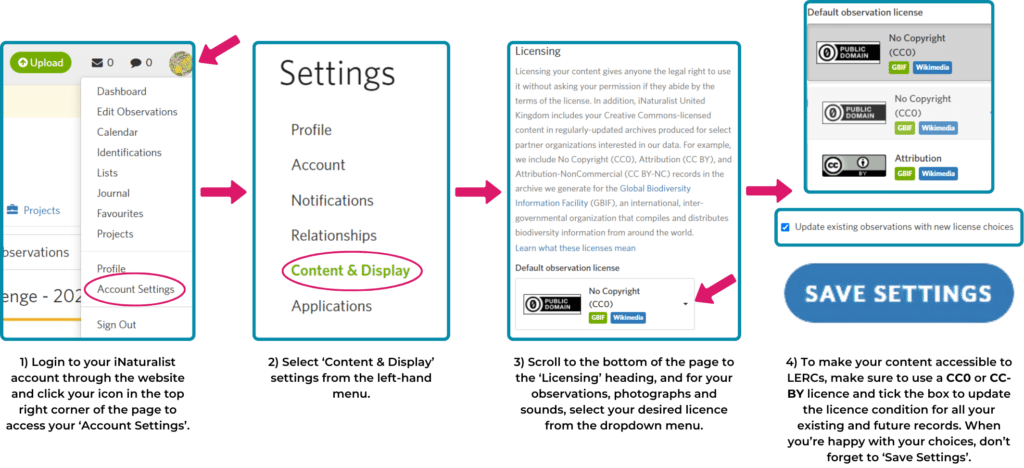

Because iNaturalist has been designed with the explicit intention for the transfer of data from the users’ phones to GBIF, there is seamless integration between these systems, a serious time-saver for data managers. As default, records are attributed with CC-BY-NC licences (known as ‘shared data’), but in order for records to move from iNaturalist to iRecord and beyond to the NBN Atlas and LERCs, licences which permit commercial use must be in place e.g. CC-BY (known as ‘open data’) or CC0 (known as ‘no copyright’). It’s possible to licence observations, sounds and photographs separately.

To ensure that your records can be used by GiGL and its stakeholders, follow the simple steps below:

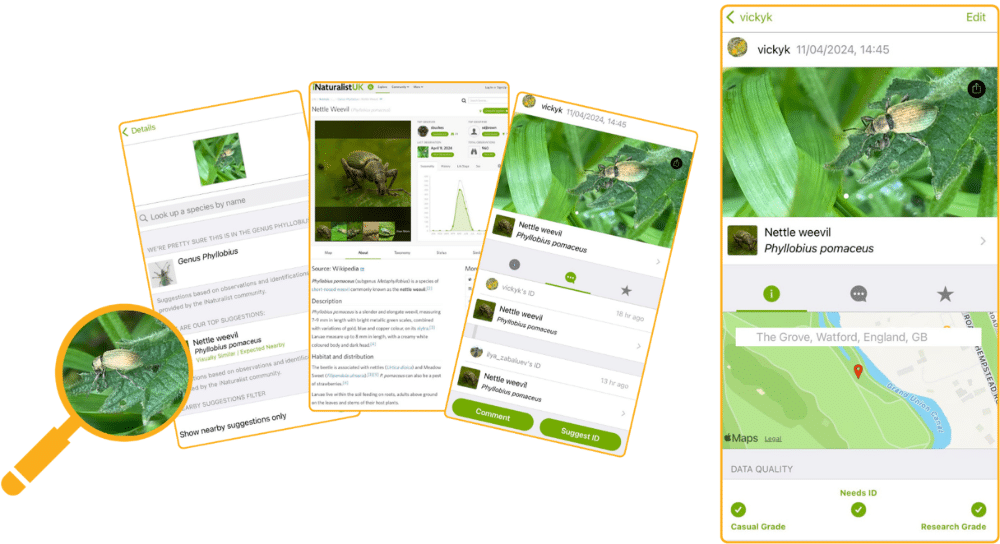

iNaturalist data now also feeds into iRecord once a record has achieved ‘research grade’ – the condition in which at least 2/3 iNaturalist users have concurred on the same identification of a record, as well as meeting other basic seasonal and location sense-checks. While the potential for misidentification might drive experts mad and does indeed pose a real threat to data quality, the chance to get things wrong, be corrected and promote discussion should not be undervalued as an engagement tool – and a fast-acting one at that: at the time of writing, the median time taken to receive an ID from another iNat user is just 3.8 days [3].

GiGL and other LERCs obtain data from iRecord, so many iNaturalist observations, where appropriately-licenced and validated, eventually feed into our species data holdings through this pathway.

Another real and understudied limitation to the use of unstructured community science data is the lack of information on ‘survey effort’. As most iNaturalist users employ it for opportunistic and one-off sightings, using data from the app for scientific studies is likely to provide biased results for many taxa and many geographic regions. To ensure data are as useful as possible, where the chance exists it is better to contribute to structured surveys such as running a BioBlitz. iNaturalist can still be a useful data collection tool where users can submit sightings to specific projects.

What really sets iNaturalist apart is the incorporation of the AI Seek software – an impressive computer vision model that suggests species identifications based on the images provided by the user, referenced against the database of images sourced from other iNat users and weighted by any accompanying spatiotemporal data. The more the technology is used, the better the image recognition can become. It is not only a brilliant feature for beginners, it’s also an important verification tool as images can be vital for settling an ID dispute, especially for new arrivals to the UK or difficult taxa like the bryophytes featured in last month’s Joy of Recording article from Cassandra Li, helping to reduce the ‘verification burden’ on verifiers. For some species, a specimen will always be required for effective identification and the iNaturalist suggestions should be taken just as that – suggestions as a base from which to continue investigations, rather than a definitive ID. Another significant benefit to the photographic requirement of iNaturalist or Seek is the potential to glean extra ecological details for the record, such as the surrounding habitat type or organism behaviour and combining this with location and date/time metadata which forms the basis of a biological record.

There is an option to just use Seek from iNaturalist rather than the iNat app, so you can obtain a real-time ID suggestion without the need for an account, making it a great tool for inspiring children with nature that they can name.

From left – right: Sawfly (potentially Aglaostigma aucupariae), Common Flower Fly (Syrphus ribesii), Garlic mustard (Alliaria petiolate), European Nursery Web Spider (Pisaura mirabilis), Red Deadnettle (Lamium purpureum), Coccinellidae, Western Honey Bee (Apis mellifera), all taken by Victoria Kleanthous.

Not only is the incredible library of iNaturalist images publicly available (subject to licencing restrictions), iNaturalist accounts can be linked to Flickr, making uploading photos even easier and giving users the chance to showcase their photography.

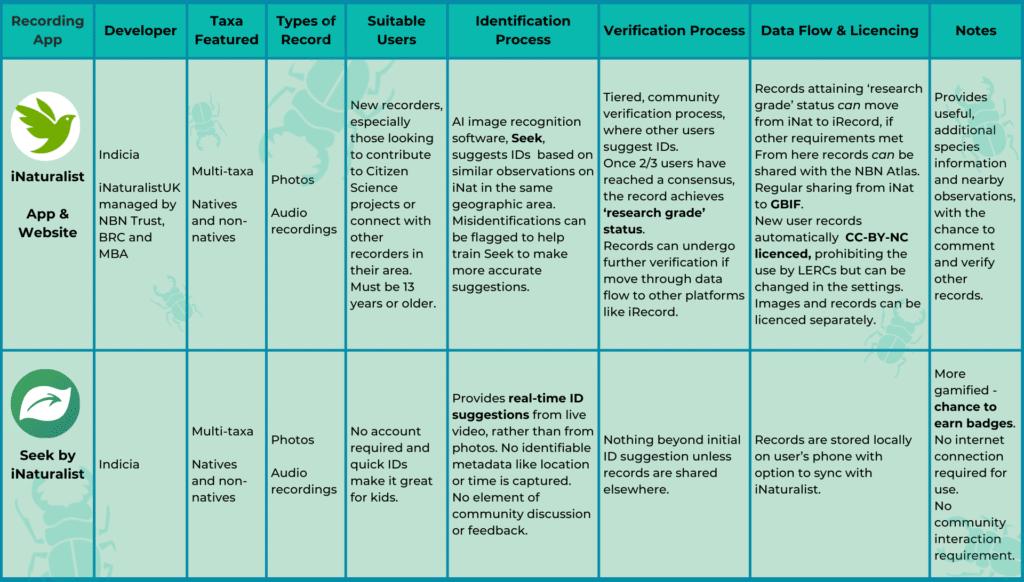

The sharing of photos helps to fuel the community feel of the app and being able to visualise your records in the local context of what other users are recording encourages the gentle competition to motivate exploring your local patch. It’s also easy to directly log observations as part of large-scale projects, such as the upcoming City Nature Challenge 2024, imbuing an immediate connection to the worldwide recording picture. So, what are you waiting for, join the fun from 26th – 29th April! The table below breaks down some key facets of iNaturalist which I will compare with other RAs of the coming months.

[1] https://www.inaturalist.org/pages/network-join , accessed 11/04/2024

[2] https://www.inaturalist.org/pages/network-join, accessed 12/04/2024

[3] https://www.inaturalist.org/stats , accessed 12/04/2024

Very useful and informative. I have changed my iNat settings to ensure data transfer/use is possible by GiGL, iRecord etc

I am sure many users do not realise their iNat data can be used across a much broader platform. iNat is very user friendly and although it has limitations (providing mis-leading data on more unusual/exotic species which are more likely to be photographed than “common” species), it has to be seen as an important tool in the “recording kit”