London, particularly south London, is lucky to host the stag beetle (Lucanus cervus) as a resident invertebrate. It is surprising that Britain’s (and one of Europe’s) largest terrestrial beetle calls the capital its home and seeing your first male stag clumsily careen towards you, mandibles akimbo, no clear destination in sight, can certainly come as a bit of a shock. It is even more surprising that despite the species’ decline across Europe and its rare status in most of the UK, London hosts a nationally significant population.

Between around May and August each year, GiGL receive hundreds, if not thousands of stag beetle and lesser stag beetle records. At time of writing, we hold over 42,000 such records. 42,000! Over 12,000 of these records have come from sightings submitted to the London Wildlife Trust’s Stag Beetle Survey, ‘Staggering Gains’, running almost annually from 1997 to present day. While Londoners today might go mad for stags each summer, without the passion and work of the great urban ecologist Mathew Frith, who sadly passed away in August, the city may never have been rocked by ‘stag beetlemania’. The story of how these marvellous beetles came to represent almost 0.5% of our total species database today spans the history of GiGL, embodies the strong professional and personal bonds that tie GiGL and the Trust together and is testament to Mathew’s commitment to both London’s wildlife and its people.

Mathew inspiring visitors at Wathamstow Wetlands.

Over the years, Mathew diligently submitted some brilliant photographs to the Staggering Gains web portal. Left to right: male stag beetle, female stag beetle, lesser stag beetle © Mathew Frith.

To protect a species, you first need to know where it is. The life cycle of a stag beetle makes understanding their distribution complicated; stag beetle eggs are laid underground near a source of dead wood and the larvae can spend up to seven years underground before emerging as adults. Stag beetles are saproxylic species, meaning that a significant portion of their life cycle is dependent on dead wood – deciduous dead wood like oak and elm being favoured. The decline of dead wood habitats in ‘tidying up’ of parks and gardens is thought to be a key reason for the stag beetle’s decline. As they feed, stag beetles aid decomposition, making nutrients re-available to the litany of decomposers present in soil, and then on to growing plants and fungi. While they might be feasting away for years, unless you happen to dig up a larvae, there are limited ways to effectively and consistently detect stag beetle larvae underground.

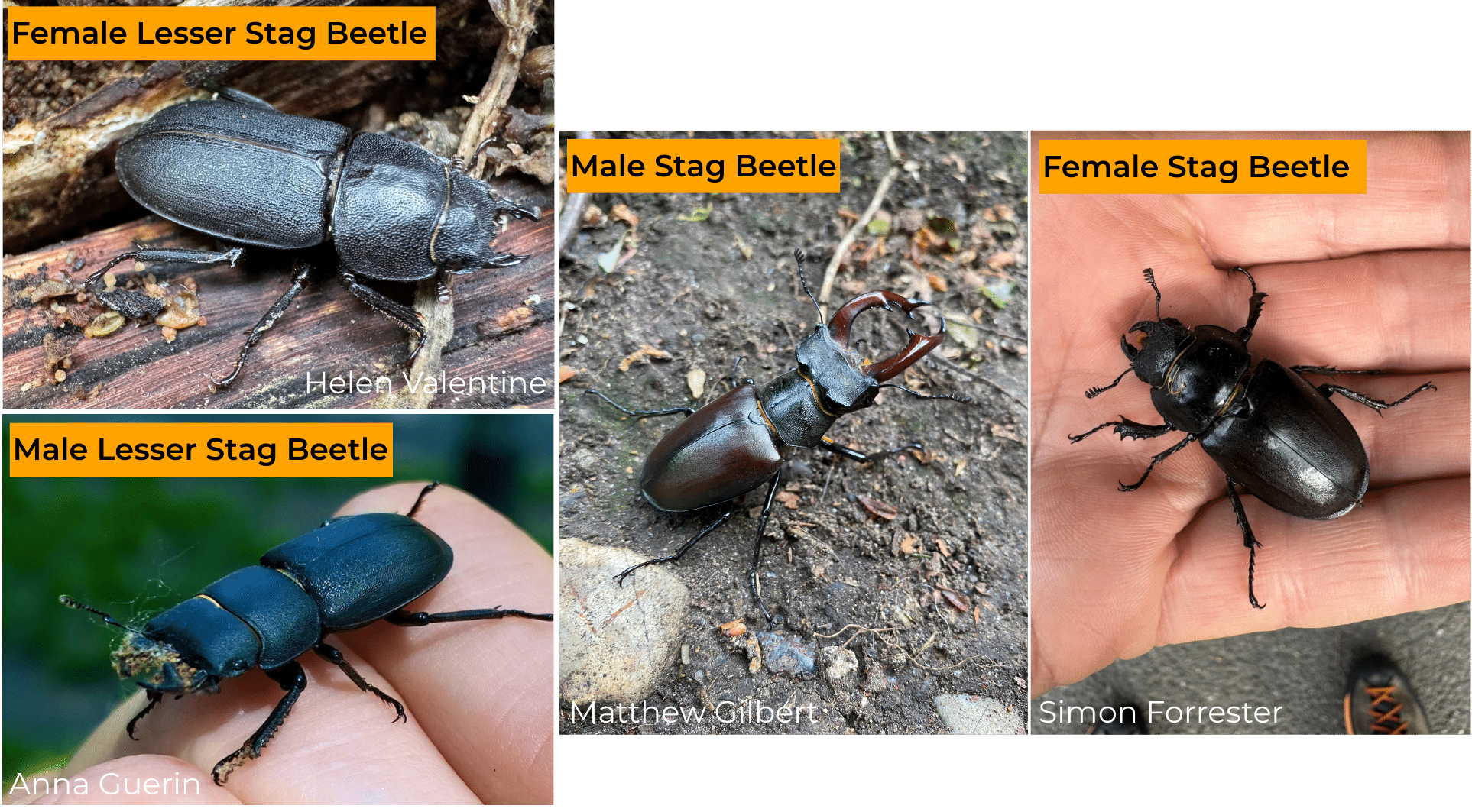

The presence of the smaller but similar lesser stag beetle (Dorcus parallelipipedus) further complicates forming an accurate assessment of the species in London. Adult stag beetles are significantly larger than the lesser, with a brown tinge and an overall rounder shape, but due to their smaller size and lack of serious mandibles, female stag beetles are often confused with lesser stags. The ‘antlers’ on the male stags are a bit of a giveaway though.

Note the larger size, different colouration and general shape between lesser stag beetles (left) and stag beetles (right).

Difficulty in finding and identifying stag beetles and their declining population across Europe, meant that by the late 1990s, there were very few records of stag beetles in the whole of the UK, let alone London. But as the 1992 Convention on Biological Diversity thrust species conservation onto the global stage, the moment for a most charismatic beetle had come. Stag beetles were listed as a priority species in the UK Biodiversity Action Plan in 1995 and became a key focus for the influential London Biodiversity Partnership formed in 1996. A Stag Beetle Focus Group led by the People’s Trust for Endangered Species soon began to develop and implement a UK Stag Beetle Action Plan. This began with a London-wide survey managed by The Trust in partnership with LB Bromley in 1997, and lead to the creation of the London Stag Beetle Advice Note. The Trust had already pioneered large-scale citizen science recording projects targeted to the general public with the ‘Owl Prowl’ and ‘Kestrel Count’ and they believed the same could be done with stag beetles – though, as Mathew recalled in his 2021 London Recorders’ Day presentation, there was more than a little scepticism from esteemed coleopterists about the layperson’s interest and ability in identifying stag beetles. 42000 records later however…

The original baby pink survey form!

Mathew had been working as the Sydenham Hill Wood Warden for The Trust, learning firsthand the importance of dead wood and its decomposition for the functioning of the urban woodland. Though GiGL was in its nascent form as the Trust’s Biological Recording Project, it was at this time that would-be GiGL CEO Mandy Rudd, and Mathew Frith first met.

“I first met Mathew Frith just before I joined London Wildlife Trust in July 1997. I was working in a print shop that the Trust used, and was asked to deal with someone coming in to get some survey forms photocopied. That someone was Mathew Frith, and the forms turned out to be for the first stag beetle survey conducted in London. I showed Mathew what I thought were appropriate colours of paper for a conservation project, and he rejected all of them. He chose baby pink.”

The forms were a hit! The survey was advertised extensively on the radio, in local newspapers, community centres and Londoners lapped it up. By the end of the summer, over 200 records had been captured in London. Mandy, who was now working for LWT, cut her teeth plotting the results of the 1997 survey to be digitised into the first ever London stag beetle GIS dataset.

“…One of my first projects was to take the completed survey forms that had been sent out and returned by post, and to plot the locations of stag beetle sightings in red felt tip on photocopied pages of an A-Z. These paper-based distribution maps were then ready for digitising on the newfangled GIS by Alistair Kirk, who headed up the Trust’s Biological Recording Project at the time. Mathew took a keen interest in the paper-based results, and I can distinctly remember him taking the time to tell me all about his ambitions for the remnants of the Great North Wood in south-east London, and why stag beetles were such an important species to champion. He loved reading all the stories that survey participants had shared alongside the form, from survey participants who had followed the Trust’s advice on managing their gardens to create stag beetle habitat, to a man who was convinced the same stag beetle was returning to visit him in his garage year after year.

I successfully applied to be the assistant on the Biological Recording Project later that year and became part of the Trust team that helped the PTES run their national stag beetle survey in 1998. There was a lot of interest from the media, resulting in more stories being sent by letter to the Trust and a (hopefully dead when it was posted) stag beetle arriving in a Jiffy bag addressed to me. The survey launch was held in Richmond Park and attended by Michael Meacher, Minister of State for the Environment at the time, as well as a lot of journalists, so it was all hands-on deck. Mathew and Emma Robertshaw, the Trust’s Communications Manager, decided I was best placed to be driven from the launch to the ITV studios on Southbank to be interviewed by Mary Nightingale live on the lunchtime news. It was an enormous relief that we were unable to find a live stag beetle for me to take to the studio to show viewers, instead I was sent off with a plastic one that I shakily held out on air. I didn’t forgive either of them for the ordeal for a very long time”

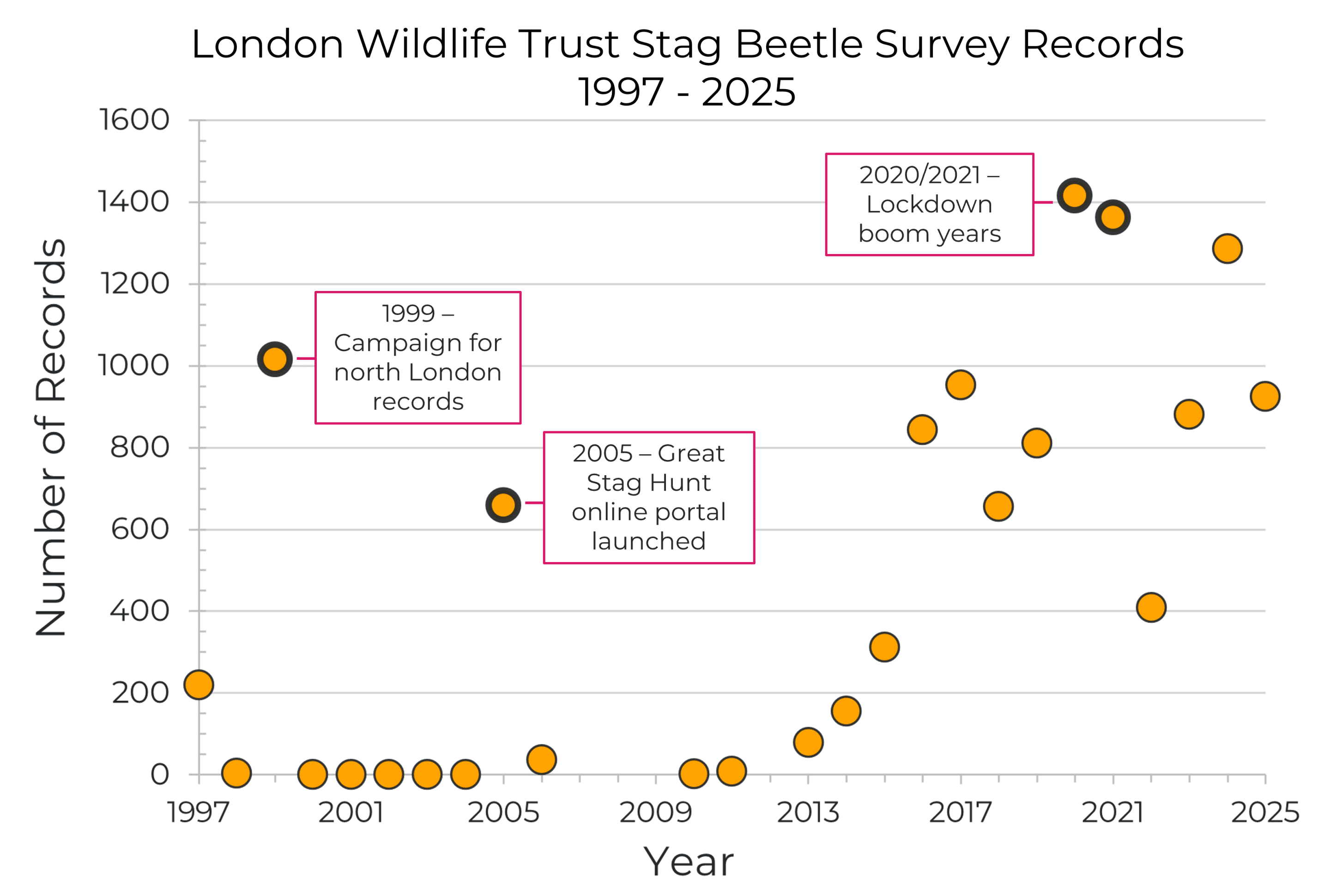

Since the original 1997 London survey, there have been huge increases in record numbers, with noticeable peaks in 2005 and the lockdown years.

The success of the 1997 London survey was repeated in the national survey led by PTES in 1998 (not included on the graph). From the two datasets, London, specifically south London boroughs Richmond, Wandsworth, Croydon and Bromley were emerging as a hotspot for stag beetles. A 1999 survey was targeted in north London to investigate whether this was a genuine result or an artefact of recorder effort. An effective comms campaign inspired north Londoners to report their findings to the Trust. While populations of stag beetles were found in specific sites like Epping Forest and Hornchurch in Havering, there was a noticeable absence in northwest London and an unmistakeable concentration in the south.

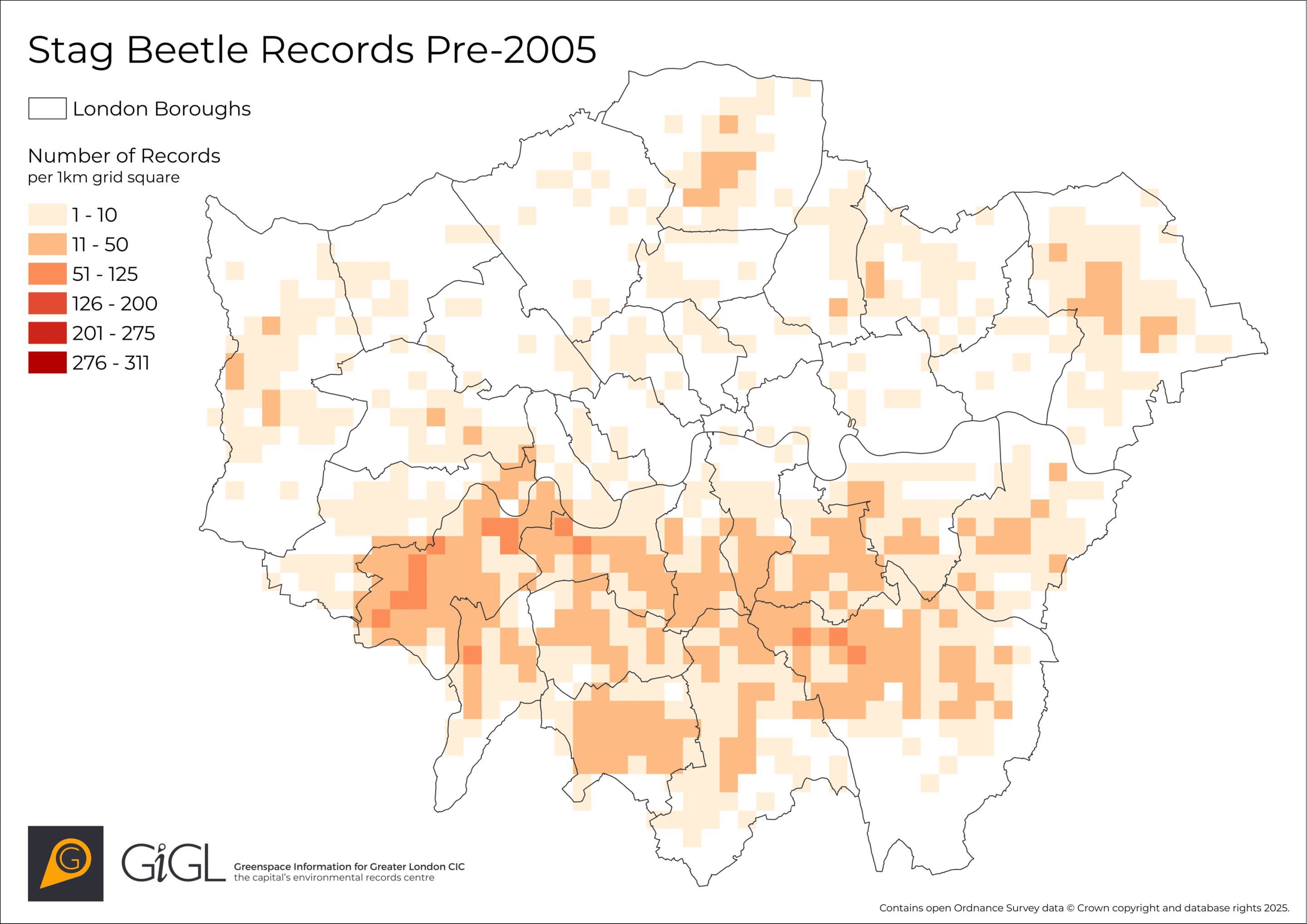

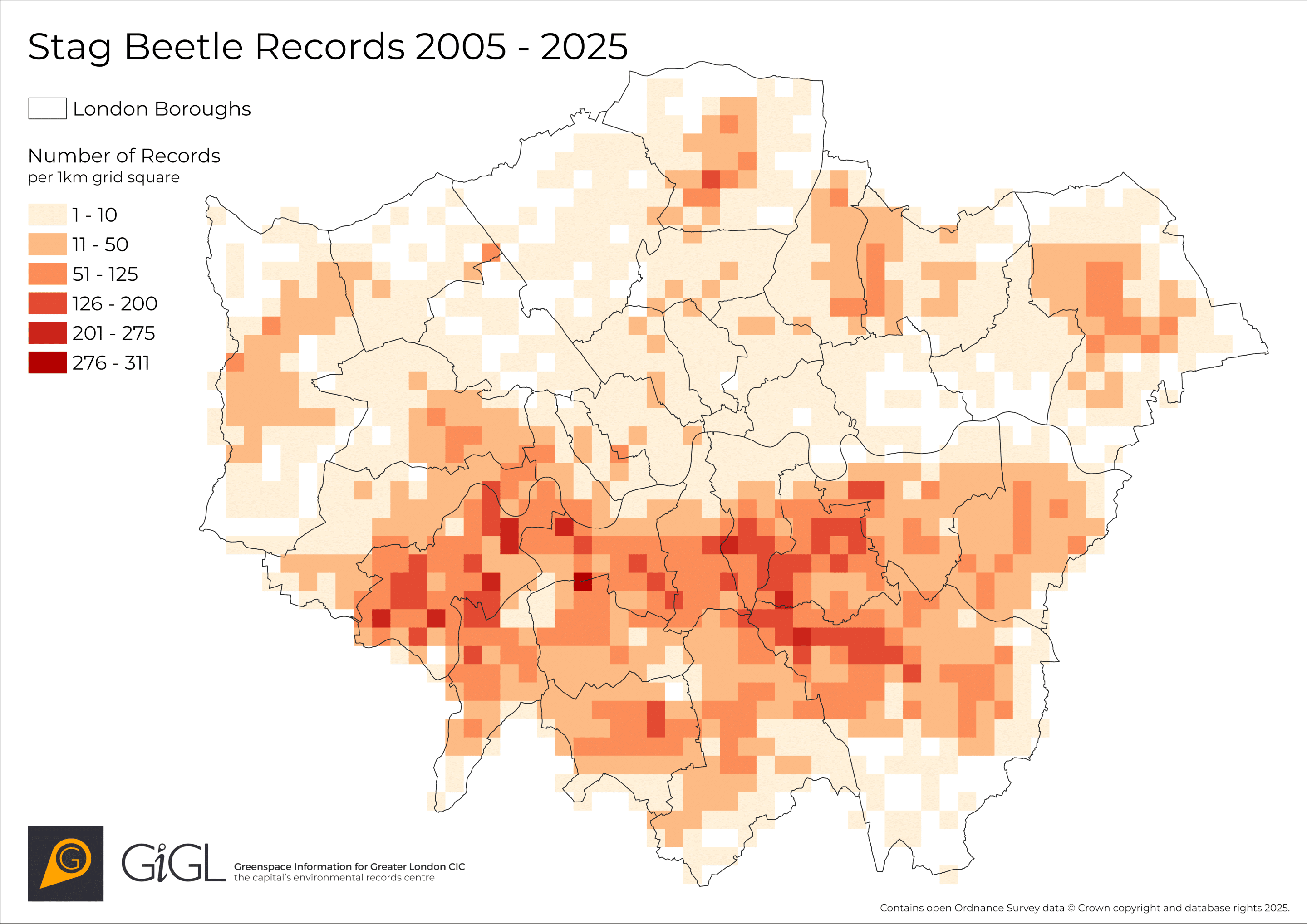

A before and after comparison of heatmaps showing the number of stag beetle records received pre and post 2005. These maps include records from the LWT survey as well as other sources.

As the two heatmaps show, the same pattern of records has repeated again and again – dense records in south London, an absence in the centre where there is insufficient habitat and only scattered localised clusters in the north of London. There are a few competing theories for the distribution, including the female stag beetle’s preference for sandier soils in which to dig, the abundance of garden land in south London and perhaps something to do with the original area of the Great North Wood. As the favourite GiGL adage goes ‘an absence of evidence is not the same as evidence of absence’, and the more records gathered by surveys builds up an ever-clearer picture, helping to rule out recorder bias.

In 2000, the findings of the survey were instrumental in Mandy and Mathew collaborating on the first English Nature Advice note on stag beetles, reproduced by the Trust and GiGL in 2016. GiGL digitised the survey process in 2005 and proudly manage it as the ‘Staggering Gains’ webform. With the loss of the lovely baby pink survey forms, managing the survey online means we can verify the records more easily by checking photographs also sent to us. Lesser stags can’t fool us! We now regularly receive over 800 records each summer, and just as Mathew and Mandy did with the original survey, continue to enjoy your comments:

“We called her Teri, we love Teri”

“Flying majestically but awkwardly towards me, then flew away”

These great ‘Thunderbugs of the Suburbs’ as Mathew once coined will never fail to surprise. A great collaborator and orator, Mathew was able to mold the public’s enthusiasm into not just a successful monitoring programme spanning a quarter of a century, but also an effective education campaign for the ‘messier’ management of protected sites and gardens. Just see the myriad loggeries and buried tree stumps now visible in London’s parks. As friend and colleague Richard Barnes, head of Planning and External Affairs at London Wildlife Trust shared,

“Mathew’s passion for the weird and wonderful of the natural world, and London, was typified by his role in raising awareness of stag beetle conservation in London. From the personal (picking up stag beetles stranded on the pavement) to the professional (promoting surveying every year, and writing the first advice note with English Nature in 2000 then subsequent revisions), he led from the front. I’m sure Mathew’s tireless work has ensured their continued success in London.”

Thank you Mathew.

To submit stag beetle sightings to GiGL, use our Staggering Gains portal. For records outside of London, please report them to PTES’s Great Stag Hunt which runs across the country. As data sharing partners, data flow between GiGL and PTES.