Minhyuk Seo, GiGL Partnership Officer

Min is GiGL’s Partnership Officer and Commissioning Editor of the GiGLer newsletter. He delivers work for existing GiGL partners with Service Level Agreements, as well as carrying out work with students that wish to use GiGL data for research projects. At times he focuses on internal database work and core projects.

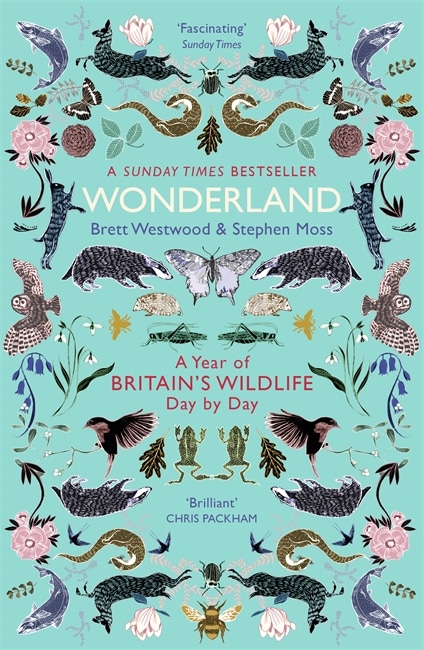

Brett Westwood and Stephen Moss are names you will have come across if you watch or listen to any BBC wildlife programmes or radio series. They are household names in the BBC Natural History Unit when it comes to British wildlife and this is the third book they have written together after two very successful attempts; their first book “Tweet of the Day”, based on their award-winning radio series of the same name, won the Thomson Reuters Prize in 2014.

In “Wonderland”, the duo effortlessly guides the reader through each day of a calendar year (including February 29th), highlighting, rather impressively, everyday a different species or a seasonal feature throughout the British Isles that they have come across in the last forty years – albeit many of them based around the authors’ home counties of the West Midlands and Somerset. It is essentially a diary; each day is characterised by a species, date and a few accompanying paragraphs (for example: MEADOW PIPIT – 6 September -…).

Nowadays before reading any book – with branding and first impressions key to any product – a book should be judged by its cover. In this book, the literary tone is preset by the idyllic aesthetics of the illustrations that adorn its cover; a symmetry of colours and prints of wildlife create a sense of wonder, befitting the title. Indeed, Westwood and Moss journey through each day recounting their personal experiences often with such poetic prose that one can confuse this ecological diary with an anthology of love-letters to British wildlife.

There is no plot to “Wonderland” per se which renders the reading chronology of the book somewhat insignificant, as each day and the species being described is clearly signposted. The days are in no way connected to one another which is both the beauty and downfall of this book; you can never “lose track” in your reading with the lack of dense material but subsequently there is no profound sense of ‘completion’ upon finishing it. Despite this, the beautiful way in which Westwood and Moss paint their personal encounters with some of Britain’s most common and rarest creatures is enough to convince any nature-loving reader to absorb every word. The book covers an array of habitat types from cities and gardens to woodland and coastlines, with species ranging from barn owls and foxes to fairy rings (fungi) and broomrapes (parasitic plants).

Wild Garlic – the species for 28th February © Creative Commons

As the authors indicate in their introduction, this book is not a field guide, but for the amateur ecologist and nature enthusiast, it is a delightful introduction to the variety of wildlife in Britain. As enthusiastic birders thus wildlife recorders themselves, Westwood and Moss stress the importance of recording nature not just with their senses but with a pencil and notepad; their noted records are usually submitted to their county Biological Records Office (i.e. their Local Environmental Records Centre) where their records become useful for others, including “informing local planning decisions”.

This message is particularly applicable to GiGL; a Key Performance Indicator for us this year is to launch a planning alert layer to aid local authorities in considering wildlife when making planning decisions – something we have worked on a smaller scale before. An overwhelming majority of our records are thanks to volunteer recorders, with nearly 60% from the London Natural History Society alone, and this book, if anything, is a celebration of life through the eyes of a wildlife recorder and naturalist.

“Wonderland” is recommended to readers with any level of interest in nature seeking some light-hearted, positive literature about modern British wildlife. For the more visually-inclined individual, the reading experience may be enhanced by the accompaniment of an electronic device connected to the internet for a quick search of what each of the described 300-odd species look like.